I conducted a brief study of case capacity and its effect on muzzle velocity this weekend. Such studies are easy because spending time at the rifle range is fun. They are also difficult because time is limited and it takes a lot of trigger time to get statistically significant results.

This study is not rigorous in that insufficient data was collected to prove any correlation between muzzle velocity and case capacity for a given brand of case, but enough data was collected to show a link over several brands of cases. The difficulty here is that there is more to muzzle velocity variation than case volume, but if the variation in capacity is great enough, we see the effects clearly.

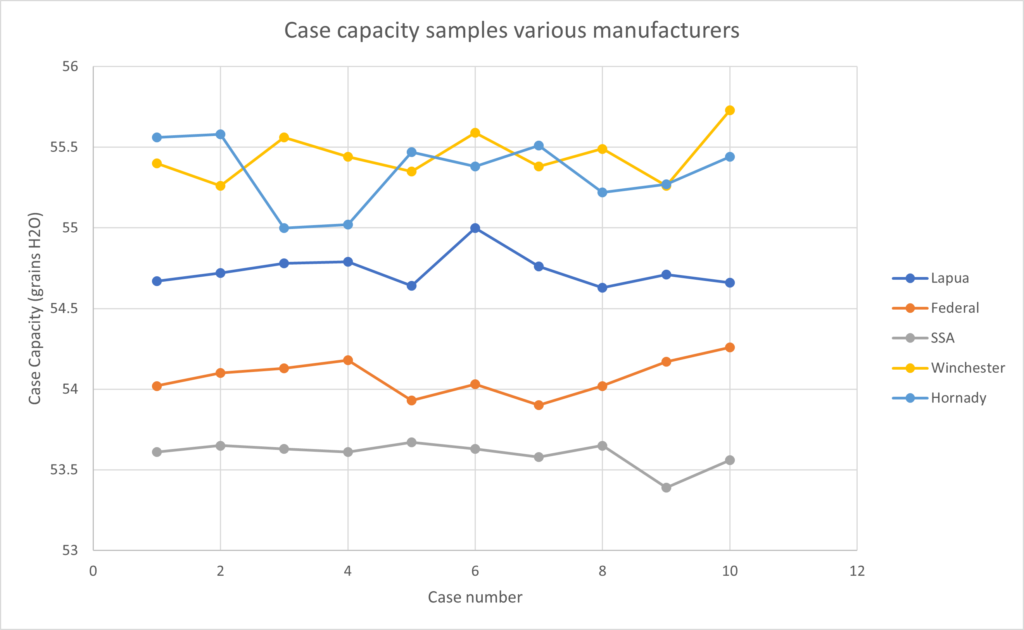

Starting with the case capacity in grains of H2O between a selection of new and once fired 308 Win brass from Lapua (once fired), Federal (once fired), SSA (new), Winchester (new), and Hornady (once fired).

SSA has the lowest capacity while Hornady and Winchester were about the same at the highest capacity. Approximately 2 grains of H2O capacity separate the lowest from the highest. We expect that all else being equal (i.e. the same powder charge and bullet weight etc.), the cases with the lowest capacity will exhibit the highest muzzle velocity and vice-versa. Here’s the results from the range session shooting off-hand with an M14 (shot pretty well, one 10-round string was 96-2x)

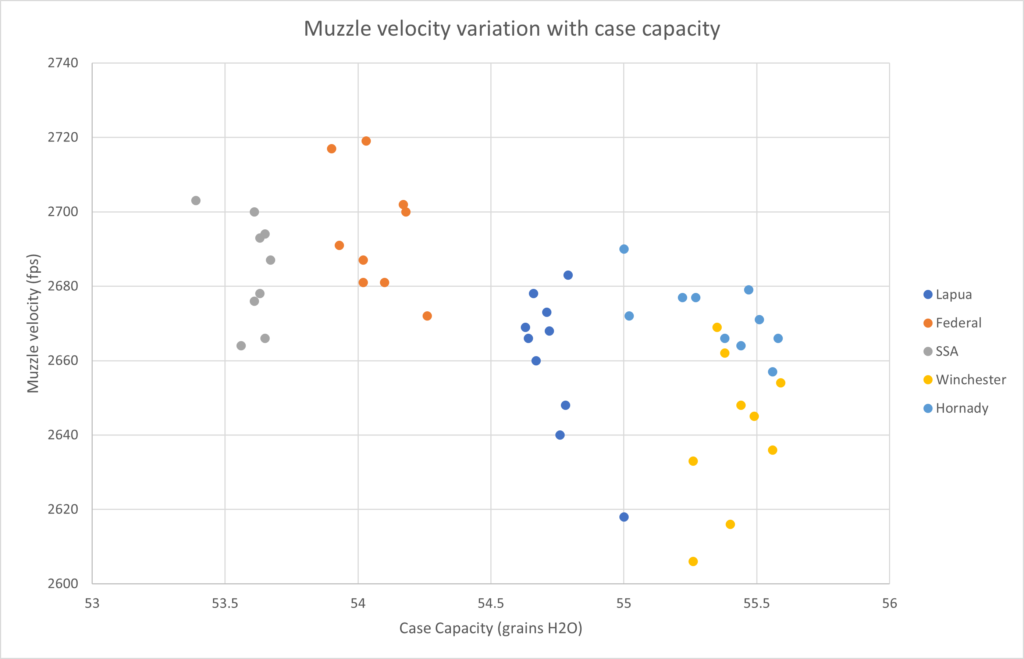

In this figure clear correlation between case volume and muzzle velocity is apparent. Obviously other factors influence muzzle velocity besides case volume as there is significant variation in muzzle velocity that does not correlate with case volume. For example, the SSA brass (grey dots) has lower muzzle velocity than the Federal brass (orange dots) even though it clearly has lower case volume, which generally correlates with higher muzzle velocity.

Given that the powder charges were thrown by an Autotrickler to 41.2 +/- 0.02 grains of H4895, the powder charge is the most consistent thing besides bullet weight at 168 grains for the Sierra Match King bullets used in this test. Notice also that for each 10-shot group except for the group shot with Hornady brass, the variation among the group does not correlate much at all with case volume. This is to be expected with sample sizes this small. Even so, the correlation among the data in general agrees with the prediction made by Quickload between 20 and 30 fps per grain of case volume, all else being equal.

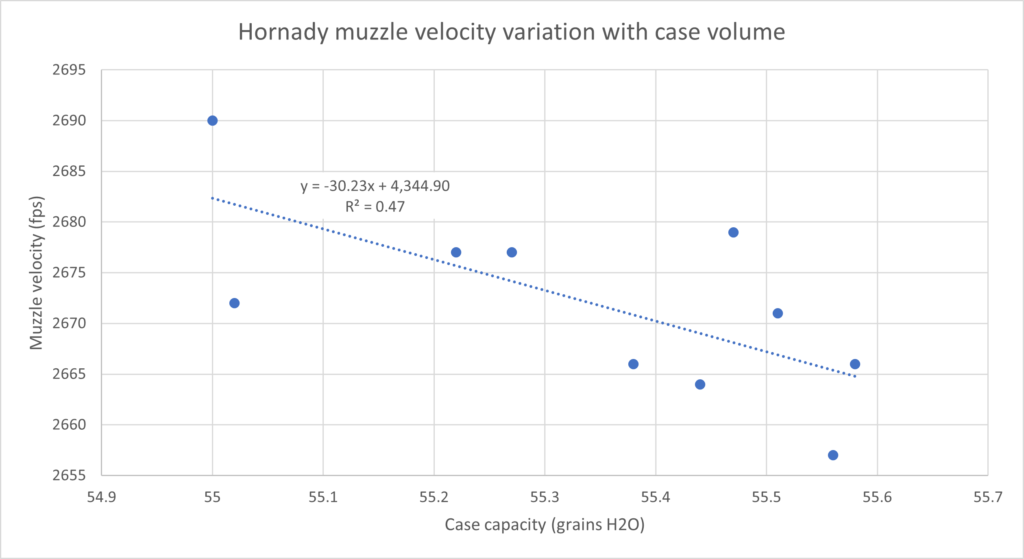

The Hornady brass did show good correlation between case volume and muzzle velocity so let us consider it more closely.

This correlates with the prediction given by Quickload but is still too small a data sample to be taken as strong evidence. And there lies the problem as always with load development and accuracy: the difficulty with which we obtain meaningful results due to the constraints involved in gathering statistically significant data. Barrels heat up, fatigue sets in, Lab Radars fail to register a shot, and so on.

Ideally I would turn necks and be very careful about neck tension, flash holes, and the rest, and then shoot 50 to 100 rounds of each brand case. I’ve also found that correlation is stronger if the volume of the fired case is measured before resizing and compared with the muzzle velocity from the previously fired shot.

So take the data as it is, a point from which we can move forward, no more, no less, and an indication that what we expect is true, so now we have to be more careful to prove it.

In an upcoming article I will discuss strategies for using case volume measurements to inform load development for match shooting at 600 yards and beyond.

Man , this is a fantastic bit of insight. I appreciate the effort for sure. Being able to push capacity a little bit in Hornady brass is good to know , as long as pressure doesnt rear its ugly head. In any event , Hornady moved up on my brass stash scale.

Good read