Countless times I am asked and have asked the question that arguably troubles rifle shooters more than anything: “How accurate is my rifle?” Most shooters, myself included, have settled on 3 or 5 shot groups, and the expected extreme spread of that group. We like to buy rifles that promise groups that are 1 inch or 1 MOA. We take our shiny new weapons to the range and put the manufacturer’s guarantee to the test.

The after-action report finds us sometimes pleased and sometimes not. We all know a single bad range trip can be due to lack of sleep, too much coffee, a bad batch of ammunition, ammunition the weapon simply doesn’t like, or one of many other excuses. These excuses might be legitimate, but there’s no way to know. Adjustments are made, bullet seating depth is changed, different ammo is selected. The next range trip might produce a couple groups in the MOA to sub MOA range and we are then pleased that our rifle is indeed a shooter and we pack up happy until next time.

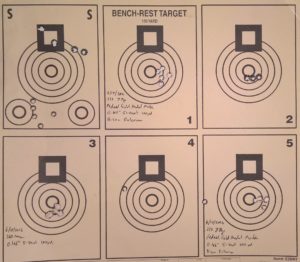

Then we get really sophisticated, especially if we are hand loading our ammunition. 50 rounds, in a blue plastic box, the first 5 sets of 5 rounds varying powder charge by a few tenths of a grain, the second varying bullet seating depth. We shoot our 10 groups and look for trends, and we see the groups open up or close down in a manner that appears to vary proportional to the change in the parameter of interest. And who doesn’t love a good looking target after a trip to the range.

I’d seen some interesting measurements of group statistics that got me thinking. Extreme spread was never completely satisfying from a practical point of view, and achieving a small extreme spread had become more like winning a football game than providing meaningful feedback about the outcome of a shooting session. Here’s where things could have gone one of a couple different directions. If I were to keep on keeping on, business as usual, keep chasing MOA and sub-MOA 5-shot groups with extreme spread as the metric, I start to run the risk of fooling myself. Fliers are the shooters equivalent of Mulligans in golf, and we use “called fliers” as a means to tighten up the group size. I find called fliers very unsatisfying and if the group didn’t stay together, it didn’t stay together and that was that. Still, not enough useful information.

Not surprisingly, all these shooting sessions, all this data, and it’s clear there’s more meaningful information. The problem of measuring shooting accuracy clearly has a statistical nature, and concepts like mean and standard deviation, already long in use when thinking about muzzle velocity, must be applicable in some way. The internet knows everything and Bing searches quickly lead to Ballistipedia. Go there and you will find the application of some serious statistical expertise to the problem of thinking about and measuring rifle accuracy. The problem turns out to be a lot more complicated and nuanced than I thought.

Once I got through my five stages of grief, having given up the old and beloved way of thinking about accuracy, serious study of the proper way to analyze the measurements of little holes in paper began. It took me a couple months of part time study, but I finally gained a good understanding of the statistics of measuring rifle accuracy. The problem is complicated and I think the subject is not one that is suitable to most shooters who just want to know the practical accuracy of their weapons so they can be aware of what shots are reasonable for them to take, and what is the probability of a given outcome.

Getting back to the beginning of this post, as a company that sells rifle barrels and components, we want to be able to tell our customers what level of accuracy they can expect from our products. Now we know there is no meaningful answer to the question “Will my rifle shoot MOA groups?” The hope is for a sea-change in the way rifle accuracy enthusiasts think about and discuss their topic. The methods presented at Ballistipedia are correct but not generally accessible, and the practical implications of the results of detailed statistical analysis of shooting data are hard to discern. A system is needed that boils down the results of the statistical analysis of a sample of shooting data into different classes of performance. Once a weapon and ammunition combination has been classified, the shooter can easily assess the likelihood of a particular outcome of a hypothetical scenario. The shooter can know how likely they are to shoot a 5-shot group with MOA or better extreme spread. They can also know the probability of any given shot being within 1/2″ from the true point of aim. They can also know how many shots are needed to get a good estimate of the true point of aim of their weapon so that they can achieve a good zero for their scope.

To this end, Bison Armory has worked with Ballistipedia.com to create the Ballistic Accuracy Classification system.

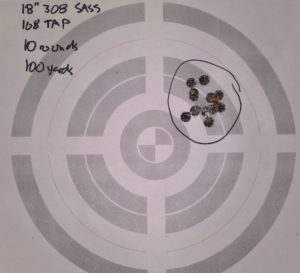

We are still working to classify our barrels, upper assemblies, and rifles, but to start we guarantee that our products are at least Class 5 as defined in the BAC system. In practical terms, this means a shooter can expect at least 39% of their shots to fall within 1/2″ of the true point of aim, 9% of 5-shot groups to measure 1″ or better extreme spread, and 35% of 3-shot groups will achieve this measure. Our data indicates that our products are probably typically Class 4 but we’ve not gathered enough data yet to make a guarantee i this regard. For Class 4, a shooter can expect 54% of their shots to fall within 1/2″ of the true point of aim, and 26% of 5 shot groups will have a mean radius of 1″ or smaller, and 57% of 3-shot groups will be this small.

Our match grade, heavy barreled, and Fulcrum products should approach or achieve Class 3 status with the right ammunition. Of course, the true classification of a given barrel in practice will depend on the quality of the build, the ammunition used and its suitability to the weapon, the setup and performance of the shooter, the trigger, the total weight of the weapon, the quality of the optics, the tightness of the fit between upper and lower receiver, and other factors.

Once you know the class for your weapon, you can know with confidence important metrics like the probability of hitting a given target at a given range with a single shot.

No other rifle manufacturer we know of goes to these lengths to give a meaningful accuracy guarantee for their products. It takes time, it takes commitment to the truth above marketing, and it takes dedication to rifle shooting as a discipline. Don’t be fooled by phony accuracy guarantees. Demand the truth, embrace the truth, and then every shot will count.